That Strange Sensation

The End. Part Ten.

Starting the next day, Caroline and the rest of the Directive (the group’s new name for the director-worshippers) begin snorkeling recklessly in the waters of Apocalypta. After each excursion, they emerge on the shore shivering, sometimes vomiting, their expressions pale and vacant.

Upon close inspection, the Directive discovers the crates are attached to a concrete platform in the seafloor by thick, rusted, metal chains. In short, they cannot be moved. Just to complicate things, each crate apparently has a combination lock attached to it, preventing the top lid from being pried off.

Caroline’s group fiddles with these locks a bit, and tries to figure out other methods of opening the crates too, but they’re ultimately unsuccessful. Their work is hampered by the fact that they can’t last ten minutes in Apocalypta without beginning to feel violently ill.

Paul, George, Tess, L, and Ivy sit on the beach numbly watching the Directive take shifts throughout the day. They venture out in groups of three, rowing close to the dark waters—Paul, L, and the others forbid them from taking the boat into Apocalypta—before jumping out, going for a short swim, then weakly rowing back to shore to be replaced by another group.

“If we can’t bring the crates to us,” says Ivy toward the afternoon, as they eat yet another lunch of rice and beans, this time with some wild amaranth, “could we establish some kind of safe passageway to the crates?”

The group determines it’s not a bad idea. That way they wouldn’t have to clean the whole of Apocalpyta, just a narrow pathway. They begin to envision a sort of roof-less tunnel, some kind of barrier in the water. All the methods they can think up are imperfect. They do not have concrete, nor steel, nor any other impermeable wall-building materials. Plus, the shallowest part of the water out near the crates is still at least five meters deep, so if they were to build some kind of retaining wall, it would require a heck of a lot of material.

Over the next four days, they spend a lot of time planning, arguing, and discussing. The only actual progress they make is that they successfully braid together a floating bamboo garden bed. They fill it with plants they find around the island that have daily contact with saltwater and seemed to thrive in it.

On the final day, when there are only a few hours left in the whale’s timer, they row out to Apocalypta and push the garden bed toward the border. Then they ask a Directive member to use a long rope to anchor the bed to one of the crates. That way it won’t float off into deeper Apocalypta, and they can monitor its progress, watching for any paultsakes, which Paul reckons should form within a week if their experiment is successful.

When the timer goes off, all thirty-five residents of the island are watching the whale from the shore. It is mid-afternoon with a hot sun and they bake, unwilling to move into shade and miss what might be the end of the world. At the moment of 0:0:0, the bryde whale breaches, arching high in the air, leaving the water entirely, before slamming back down, sending a huge wave their way. By the time the wave reaches them, the whale has gone under. It does not reappear.

The Directive moans and wails and begins performing their rituals. They catch and eat a snake. Finally, L is able to observe their fishing technique. They track a snake into its hiding place under a rock. Quietly, carefully, they use surrounding rocks and coral to build a pathway. Then one of them lifts the rock at an angle, opening the side facing the pathway. The snake darts out, and, unable to engage in its natural zig-zag swimming style, it swims directly into the baseball cap that Jason has set as a trap at the end of the tunnel. Then, with Jason’s raw, savage bite into its middle, it’s lights out for the purple snake.

In any case, by evening, the Directive is exhausted, quietly crying and grieving on the beach. Everyone else has moved on.

“I knew it,” Tess allows herself to say. “I knew it was a trick.”

“I guess so,” says L, though she has a sinking feeling that with this failure they are now trapped here. Maybe forever.

*

Five years later. There are twenty of them left. At least ten died from radiation poisoning, with several causes of death ambiguous—did Caroline accidentally get knocked cold by a coconut, or was she inattentive to the sound of the heavy fruit snapping off the branch, lethargic as she was by then? Did Jason die from the flu, or had his immune system been compromised from the radiation poisoning? That one was hardly a question anymore. It was only the few survivors of the Directive that asserted the ones that died from common illnesses had had bad luck and not poor judgment.

There had been three suicides, and they weren’t the people you might’ve expected. The ones who gave up had a look in their eyes as if they could never really settle into the delusion that was their reality. You had to be a bit crazy to survive, was the thing. The ones who were too attached to their normal lives, too comfortable with their natural points of view, were the ones that couldn’t cut it.

It took three years to clear a safe pathway to one of the crates. Paul’s mushrooms worked, but slowly, especially at first. Initially, they only had the few beds, which did indeed become thick with paultsake mushrooms, especially once they figured out which plants were best for paulstake cultivation. Once the tightly braided bamboo walls, thick with oyster mushroom mycelium mats, were put in place, the group really began to have some hope. But it was the snakes that finally ramped up the pace of removal of radiation, oil, and heavy elements.

On one of Jason’s last expeditions to Apocalypta, he’d discovered that the purple snakes seemed to love the paulstakes. One had heaved its little body up into the garden bed and was chowing down. Another few had attached to the walls.

Once L started breeding the snakes, the paultsakes could be cleared out more readily, and so they began to produce more often too. Over the course of a year, the water, slowly but surely, went from completely opaque black to a slightly translucent dark gray with a shine of green. By the end of the third year the water in between the bamboo walls and floating garden beds looked similar to the Hudson River. You wouldn’t want to swim in it, but it didn’t look like you’d immediately die either. Once the radiation had gone down to .3 sieverts, they began taking daily trips out to the crate.

One day, about six months into these trips, Brendan motions that he wants to join them. They don't think too much of it. As soon as he swims up to the crate, he puts in a code and opens the lock.

“What the hell, Brendan? How the fuck?”

He shrugs, as if to say that to explain it via hand signals would be impossible. Then, he pries the top open. There is nothing inside.

*

When they get back to shore, a man is waiting for them. He wears a fancy button-down shirt and gray slacks. He’s taken off his shoes, which are a freshly shined pair of loafers. No one new has arrived on the island for four years. And this man does not sport the expression of a new arrival—he doesn’t look confused, or weakened. He is smiling.

“Uh, hi?” says L.

“Hi! I’m the director! Congratulations, you won!”

“We won?” asks Paul.

“Yeah! You figured out how to clean up that nasty, nasty water out there and open the crates!”

“Yeah,” says Ivy.

L’s heart is pounding. She's angry. She looks around. The others seem to be having similar reactions.

“So, what the fuck do we win, then?” says Ivy.

“Well, you will be written up in our scientific journals and awarded the patent for this ecological clean up system you’ve created!” He's cheery.

Paul laughs. “Your scientific journals? In the year…”

“Oh,” the man says. “I’m from the year 2140. Basically, by my year, climate change has really gone off the rails. It’s really bad. Everything’s hot and polluted.” He frowns. “I’m lucky enough to have survived. Basically, most of the people left are lucky, like me. Wealthy, I mean.” He half-smiles. “So a group of us men… and some women”—he winks at L—“decided to throw a little competition between us. To see if we could gather scientists from the past to have like a little hackathon. We figured if we could get you guys to come to some sort of situation where’d you’d have all the tools you need and you’d really feel the pressure to succeed, maybe you’d finally learn how to fix some of the problems that are leading to the destruction of Earth, ya know?”

“So,” says Tess, speaking slowly. “This was all a game for rich people in the future?”

The director laughs. “Well you could put it like that if ya wanna! But, haven’t you guys learned stuff here? I’m hoping you’ll take that back to your time and put it to use! And then maybe the Earth won’t get so fucked up, ya know?”

“Well, what if we do? What happens to your timeline?” Paul spoke in a biting tone, as if implying he hoped the director's timeline would be obliterated.

“I’m not sure,” the director says thoughtfully. “Probably, though—what most seem to think—is that my timeline will stay as it is. Our biggest hope is probably finding another planet to be honest. We're not as lucky as you all. If you guys change things, you’ll probably just sprout another timeline.” He shrugs. “A better one hopefully, which you’ll live out.”

“So just to sum things up,” says Ivy. “You forced us here without our consent. Ten people have died.”

“Oh I’m not sure they died back in your timeline, though.”

“You’re not sure? Wow. You are realllyyyy a dick, sir,” says Tess.

“Yeah, yeah ya are,” says Paul.

"And all that shit with the whale was just to fuck with us then?" L asks.

"I had to find a way to increase the pressure! And it worked, didn't it?" He grinned falsely. "Now you all know things you can bring back to your world. I might've saved your whole timeline!”

"YOU might have SAVED OUR WHOLE TIMELINE?" yells Tess. The whole crowd begins screaming at him. It’s as if all their anger, all their confusion from the last three years, is finally able to be released now. The man tries to keep up a smile at first, tries to calm them down, but when they start surrounding him, he gets a panicked look on his face and suddenly, loudly, claps his hands.

*

When L returns, she is in her bed. She looks at her phone. A phone, holy shit, what an amazing device. It’s 9am. There are three messages from E. The first says. “Are you okay? Check in.” The second says, “My God, I hope you are just sleeping. Let me know when you wake up.”

The third is from a few minutes ago. “L, for the love of God, are you better? Are you coming in today? Should I come by and see you?”

She’s late for work. She texts E. “Be there soon.” Letting herself move forward on autopilot, she washes her face, dresses, and gets on her motorbike.

On her way to work, she sees the dog that she remembers lunging at her once. He’s zonked out on the side of the road. The sound of her motorbike makes him lift his head. As she passes, he wags his tail.

When she walks into the lab, E gets up. “Oh, honey how are you doing?”

“I’m okay, I think.”

“You worried us so much yesterday—you were so pale when we got out of the water.”

“Yesterday? Wow.”

“Yes, yesterday, you were acting so strange, too. Barely speaking. I was so afraid.”

“And then I went home, I guess? I didn't enter any data?”

“You don’t remember, honey? Oh no.” E examines her face. “You look better today, though. In fact, you look very very tan. And skinny!” She picks up L’s wrist. “Oh, you’re too skinny!”

“Well, I’ve basically just been eating legumes for a long time.”

E looks at her confused. “We eat pad see ew all the time, honey. I think there’s something wrong. I think you need to go to a doctor, it’s not good to lose weight like this so fast.”

“Okay, I’ll go to the doctor. Tomorrow though. I want to get in the water today.”

“If you say so.” E shrugs.

Their research that day goes fine. After an hour of counting coral, when L ascends, she feels no hint of that strange sensation. All is normal, natural, as normal and natural as things can feel after you've spent an extended amount of time underwater.

That afternoon, after they’ve entered the day’s data, they walk up the street to the neighborhood’s best restaurant and eat some pad see ew. It tastes immeasurably good. L orders a thai iced tea as well, and inhales it in a couple sips. She feels fortified.

They sit there silently for a moment. E is watching an American Western on the TV, which is behind L’s head.

“E,” she says. “I have to leave next week. I need to meet a man named Paul in the U.K.”

“Oh, is it a boyfriend?” she says distractedly.

“I don’t think so. Although, there were a few nights we were... a comfort to each other.”

“Okay, then.” E purses her lips and nods. “Well, how long will you be gone?”

“I don’t know. Paul and I, we have a lot to figure out. We have to figure out how to stop climate change. We have to figure out how to clean up our oceans. I think mushrooms will help. We'll have to meet up with Tess, and Ivy, and the others, too. And then, and then…” L finds herself slightly breathless. “And then we have to figure out how to stop all the rich people from losing all sense of morality and ethics and consolidating power to the point where everyone else is essentially a pawn in their game.”

Part Nine

Caroline and the others surround George, holding out their hands and praying over him.

"Get him outside! He needs air!" shouts Tess. The crowd parts. L and Paul help George hobble out, followed by Tess and Ivy.

“They’re fucking crazy,” George begins mumbling once they exit into the humid early nighttime. As the last light of the day seeps out over the horizon, the jungle gets louder and louder with croaking insects and frogs, the palm and coconut trees swaying and creaking in a newly swept-in breeze. A coconut falls from a tree with a large crash.

“This is all so fucking crazy!” George continues to mumble-yell, as they walk toward L and Paul’s palm tree. “Fucking Markam? What the fuck, man? Where the fuck are we? Can someone finally just fucking tell me that?”

It’s disconcerting to see someone who’d been a de facto leader since L arrived—a week ago now? she can’t be sure—go from being so poised, so “everything is fine” to this, pale, near-drooling man, eyes wide with terror.

“Look, George,” Ivy says, almost yelling, louder than L has ever heard her. “None of us are going to make it out alive if we let ourselves get obsessed over how crazy this all is. Of course people are getting religious, adding more delusions on top of the delusions we all have to buy into just to fucking exist here. People have different coping mechanisms. But it shouldn’t change our ability to process this shit as logically as we possibly can.”

They plop down under the tree. George is crying now, tiny hasty tears, but starting to breathe more deeply. He moans.

“I wish I could've warned you all," says Tess. "I found out what was going on with them before dinner. They’ve started a new religion. They think that the Director is testing us with those crates and that timer, and that if we pass, we'll be able to live here forever, like some kind of heaven."

Paul laughs loudly. “Heaven? If this is fucking heaven...I'll tell you if this isn't the most lucid dream I’ve ever had...” L can’t help but laugh a little too, though her head is uncomfortably thick with thoughts.

"Okay, but that's not far from what we've been saying,” George says. “I mean, Tess, you suggested not long ago that this is some kind of fucking test, or trap, or something. We all thought you were basically right. That we're somehow meant to try to get at those crates."

“Yeah, but we’re not praying to some imagined director," says Tess. "We’re using the best available information we have and coming up with some hypotheses. We're guessing that those crates are deliberately placed there for us. But I'm not saying I really know anything. I'm just trying to keep my head, to act on my natural human curiosity. We’re not leaping to conclusions. We’re being scientists.”

George lets out a big audible sigh. “Shit, sorry I fucking freaked out there for a minute y’all.”

“It’s okay. It’s normal,” says Ivy.

“You know, I went to one of their services before dinner today," says Tess.

The others stare at her wide eyed.

“Yeah, they do this ritual, you know. One of them, Jason, had this dream a couple nights ago, where the name Markam was revealed to him. And he was given the idea for this ritual where they stand on the beach out there at sunrise and sunset, and, well, praise the crates and the zig-zag border. They have this whole little dance they do, full of bowing and stuff. And then, ugh—" she paused.

“What?” says Ivy.

“Well, they go into the ocean, they grab one of those sea snakes, and they cut it open." She mimes a brutal knifing action. "And then, uh, well, they eat it raw."

“Oh, God,” moans George. Paul laughs again.

“Sea snakes?” L asks.

“Yeah,” says Tess. “You know the sea snakes that dart under the rocks—they’re sort of purply? They're super fast, I don’t know how they’ve become so good at catching them.”

L has that feeling of something clicking into place again. She remembers chasing the snakes in the shallow intertidal zones when she first arrived. Something about them seemed distinctive, unique, but she couldn’t ever catch one to study it.

“You know what I think?” Tess says. “I think this whole timer thing is bullshit. Everyone is freaking the fuck out but the fact is we don't really know what it's about. Maybe I’m just suspicious because Caroline and the others think that if we don’t retrieve the crates by the time the timer runs out then we’re screwed. That we’ll go to hell or something. At least that’s the impression I got.”

“So you're saying we ignore the giant whale with the timer on its back,” says Paul.

“We don’t ignore it, but we continue with our plans as if we don’t have four days left. I mean what other option do we have? I'm not going to go swimming out there in the radioactive waters. I'm not that desperate."

"Who's going swimming out there?" L asks.

"Oh I didn't mention that? They are. They've decided that's part of the test, that the Director wants to see whether they've got the resolve to..."

"Shit," says Ivy, shaking her head.

"Yeah," says Tess. "So I think we just continue on, continue acting like scientists. Maybe we try to use the mushrooms you discovered, Paul. Because I don't know what other choice we have."

The group goes silent for a moment. "I agree with Tess," says Ivy. "Maybe Caroline and the others are right. Maybe we all die, go to hell, whatever, when the timer goes off. But we don't know. And it seems like a pretty fascist way to get us to do something anyway. All I know is that I want to figure out what the hell is going on in those waters, and that the only way I keep my sanity here is to continue to act like a regular, even-keeled person. Proceed with caution. Do no harm. Do NOT go for a bath in Apocalypta.”

Part Eight

After L’s initial excitement over the synchronicity of Paul’s discovery and their radiation-related struggles, she realizes that there are a few problems with the idea of using Paul’s mushrooms to clean up the radiation around the crates: 1) They don’t have any of the paultsake mushrooms here, as far as she knows; 2) Even if they did, how would they get them over there without getting blasted by radiation themselves?

“Maybe it doesn’t matter if we get irradiated in this world,” says Pai over breakfast. “Maybe we’ll return back to our lives completely radiation-free.”

“Maybe,” says L. “ I don’t know how comfortable I am with maybe.”

The bryde whale’s timer continues to count down and the group seems no closer to a solution by the time the timer reads "4:22:40." Four days, twenty-two hours, 40 minutes.

Paul, L, and Ivy are out on the beach watching the whale and ruminating when Tess walks up, holding a small device, her brows furrowed, her body tense with thought. “Okay, you guys--I’ve done something that might be useful.”

She shows them a TV-remote sized piece of tech that she explains can detect the presence of not just fungi, not just melanin, but both in one place. “I'm not sure it'll work, but I think it should be able to detect Paul's fungus. We'll run it along the water and it'll only go off if it detects a fungal presence and melanin in the same cubic millimeter."

L shrugs. "Makes sense to me. It's worth a try."

Tess, L, Paul, and Ivy pile into the boat and row toward the zig-zag border. When they’re as close as they can safely get, Tess turns on her sensor, and, to everyone’s surprise, casts out a long wire with a tiny floating ball sensor on the end of it.

“Fishing for mushrooms, huh?” Ivy says.

They row the boat parallel to the zig-zag border, dragging the ball sensor along the dark water. Soon, her little remote starts lighting up. “Does that mean…” L asks.

“Yep," says Tess. "If my sensor’s correct, then there are plenty of paultsakes in Apocolypta.”

"Woohoo!" says L.

“No, there probably aren't any paultsakes out there because those are what we would call the mushrooms, the fruiting body," says Paul. "I assume there is only paulstakatic mycelia."

“Yeah, okay,” says Tess. "paultsakatic mycelia."

“Okay,” says L. “So we have the mycelia out there. How do we get the mushrooms to grow? Can we grow them in the salt water?"

"No, no," says Paul. "We'd need some kind of soil out there, some kind of floating garden bed situation, maybe."

Tess laughs and runs her hand over her buzzed head.

L sighs. “Well, that sounds somewhat potentially doable. And then if we grew some mushrooms the radiation would be cleaned up?"

"I mean, you'd have to remove the mushrooms periodically. A quick grow, harvest cycle would probably remove some radiation."

"Some radiation?" asks Ivy. "How much? How long would that take, Paul?"

"Fuck if I know."

The three women sigh.

"Oh, okay," he continues. "Well I'd guess weeks would probably make a difference, assuming we could grow a whole bunch."

“Not good enough.” Ivy shakes her head. “We’ve got four days. Four days and about…” She looks at her watch. “Twenty hours.” They all exhale and go silent, listening to the water slosh and the occasional oar hitting the boat.

After a few minutes, they wordlessly grab the oars and start rowing back to shore.

*

At dinner that night, everyone shows up at the same time. Normally people straggle in over a period of an hour or two, some choosing to eat leftovers very late at night, skipping the communal meals entirely. On this evening, however, which is damp and humid, the whole group of thirty-four of them are there at 8pm sharp, chatting quietly, as if waiting for something.

As soon as the food is brought in to the dining room and set on the long, picnic-style table, a group of seven steps in front of the table and joins hands. Then Caroline, a woman with long white hair, says, “We’d like to invite everyone to join us in prayer, please.”

The others look around at each other, raise their eyebrows.

“Please, join hands,” Caroline says.

Many in the group shift their weight, look down or off to the side. A few tentatively reach out for the hands of their neighbors, some of whom awkwardly take the other's hand, some stepping aside entirely and moving toward the wall.

“Dear Director, Lord of this land, which has been revealed to us as Markam…” says Caroline.

Ivy steps closer to L and grabs her wrist. “What in the living hell…” she whispers.

“We thank you for the opportunity to live in your presence, and we thank you for choosing us for this mission of retrieving the crates from the radioactive water. We know that we must retrieve them before the timer runs out and we pray that we live up to this test. We want you to know we are willing to put our lives on the line to do what you ask. We pray that we will pass your test and be able to bask in your presence for the rest of eternity. Amen.”

Those in the crowd who'd been holding hands quickly release at the end of Caroline’s prayer. L catches eyes with George, who looks severely pale. L shakes her head in disbelief at the prayer, but George just stares. L mouths “You okay?” and then suddenly George tips over and falls, crashing on the bamboo floor and making it groan with a sound that seems to echo a collective feeling of dread.

Part Seven

The next morning is overcast, with a squall, dark and heavy, out near the horizon. Once again, L is alone on the part of the beach near the bamboo dock and metal boat. She digs her feet in the sand and looks through binoculars at the crates and the fluorescent zig-zag border, which appears even more unnatural in this gray, almost violet, pre-storm light. The wind is picking up. She feels she’s just on the verge of understanding something, as if a puzzle piece is about to snap into place, when she hears a pop loud enough to strain her eardrum. Not five feet in front of her, right at the water line, lies a tall, skinny man, wearing one water-logged boot and a scruffy pair of khaki trail shorts.

He’s breathing rapidly. He lifts his head and looks around, catches sight of her. She tenses, then quickly crawls over. Soon she finds herself parroting George, projecting a friendliness and calm she doesn’t necessarily feel.

“You’re okay,” she says. “You’re…safe.” She forces a smile.

There’s fear in his eyes. “What? What is this?” His accent is British.

“You’re in shock,” she says. “I arrived here this way too, washed up on this beach like some piece of driftwood.” She smiles. “It’s normal. For this place, I mean, it’s normal. Take a minute to get your bearings and when you’re ready, we’ll walk into the forest, just a dozen meters or so, and meet the others.”

He tries to speak but it’s clear his throat is dry. He swallows, then croaks out, “What others?”

“Scientists, mostly,” she says. “This is a sort of research station. You’ll find out more once we head to the main house and get you a glass of water and something to boost your blood sugar. My advice is to take a minute and breathe, just try to relax. You’re going to be fine. You are fine.”

I think, she adds, mentally.

He looks up at her a bit warily, then lies back again and sighs, closing his eyes. After a few minutes of deep breathing, he props himself up and then takes her proffered hand to get himself standing. Moving gingerly, he follows her into the forest.

At the main house, L learns the man’s name is Paul. She finds him a glass of water and a thick slice of banana bread. Standing in the kitchen, L feels that Paul's appearance is reminiscent of some kind of plant, or mushroom, tall and spindly, with a shaggy chestnut crown.

She hears someone out on the back porch and she peeks out to find George, tinkering with an Arduino.

“What’re you up to, George?” L asks.

“Oh, just trying to program this so it can sense what elements are in the water. I want to figure out what exactly is murking things up out there."

“Nice,” says L.

Paul steps out, and George looks up, surprised.

“Paul, this is George,” L says. “George, this is Paul, a brand new…” she pauses. What should I say? Resident? Member?... Captive? She settles on “friend,” though once she says it aloud she realizes it sounds a little culty. “He showed up on the beach less than five minutes ago.”

“A new friend!” George exclaims. “Wonderful!” He grabs Paul’s hand and shakes it heartily. “Here, come sit!”

They sit on the floor of the deck, and together George and L brief Paul on the basics. They explain that about once a week—though the rate has varied—someone new arrives on the island, and most of them have been scientists and engineers, but there are artists too, like Ivy. They tell him they don’t know why they’re here, but that all their basic needs seem to be taken care of. As if through an unspoken agreement, they don’t tell him about the whale, which had been on the other side of the island this morning.

“I know it’s a lot,” says George finally. “But the good news is everyone’s been safe so far. No crazy animals or diseases or anything. It’s almost like some kind of utopia… almost…except, of course, no one asked to be here.”

“You’re sure this isn’t some kind of trick you all are playing?” Paul asks. “You haven’t kidnapped me or something?” L pegs his accent as some kind of posh British—London, maybe, and thinks that although he sounds a little sarcastic, it’s a genuine question.

George laughs. “Yeah, I’m pretty sure we haven’t kidnapped you. Were you in Thailand before you transported?”

“This is Thailand?”

“Well, that’s what we think. Based on the fauna and flora,” says George.

L says, “I was—am—a marine biologist in the Gulf of Thailand. This place is highly consistent with what I’ve been studying for the last decade.”

Paul looks L in the eye, studying her now, seeming perhaps a bit reassured. “Well given that, it’d be a pretty crazy kidnapping,” he says quietly, finding his breath. “You would’ve had to drag me across the world under some heavy sedation for more than twenty hours. But of course that seems just as likely as whatever sci-fi psychodrama you're proposing to me now.”

“Oh?” says George. “Where were you before?”

Paul pauses, then says, “Scotland. A nuclear power plant.”

“A power plant, really?” says George. “What were you doing there? You an engineer? A physicist? An environmental analyst?”

“My—I’m a mycologist. Look—” he says, then stops, rubbing his temples. “I think I need to be alone for a minute. I’m feeling all…” he covers his eyes with his palms and massages them. “All sort of tired and fucked up.” He slaps his hands on his knees then grabs the slice of banana bread from the aluminum plate it's been sitting on. “Can I take this and go sit somewhere for a minute?”

“Sure,” L and George say, trying to sound accommodating, and George points him toward the tree L sat under when she first arrived. Paul stands up quickly and nearly stumbles off. They watch him plop down under the tree then curl up in a ball, before becoming very still.

“You think he’s okay?” George asks.

“Should be fine. Don’t you remember your arrival?” L asks.

George sighs and crosses his arms. “Seems like a lifetime ago.”

*

Paul sleeps under the tree for hours. Thankfully, the storm never reaches land, just depositing sheets of water out past the zig-zag line. While helping to prepare lunch, L notices that the noise of cooking has caused Paul to sit up, but still he doesn’t budge from his spot. After most of the others have eaten, she brings him a plate. “You should eat,” she says.

He stares at the rice, beans, and squash for a moment, then, hungrily, takes the plate and begins shoveling food into his mouth.

“You know I feel some responsibility for you,” L says, “because I discovered you.”

He darts his eyes over at her. “What do you mean discovered me? Like you recruited me?”

“Recruited? No, no, I’m sorry. I just mean I’m the first one to see you—out there on the beach. It’s the first time I’ve been the one to, you know, discover someone.” She feels herself redden.

“Sorry,” Paul says, sighing. “Don’t mean to be so suspicious. I have no reason not to trust you, I guess. Everything you all have said has made as much sense as any other theory I’ve come up with. It’s all just a little creepy, you know. Very confusing, you know?”

“Yeah,” L says. “I think I know.”

“It’s especially confusing,” he continues, swallowing a large spoonful of food and taking a deep breath, “because of what was happening the second I was transported.”

L suddenly feels a twinge of that "puzzle pieces fitting together sensation" from this morning.

“Well,” Paul says, “It was a big moment. I’d just done something that I think was going to—hell, is going to, I guess—change my entire career.”

L’s eyes lock with his. “What, Paul? What had you just done?”

“I’m pretty sure—in fact I’m damned near positive—that I had just gotten inconclusive proof that I'd discovered an entirely new species of fungi. One that could have a huge impact on environmental health in some spots, what with Fukushima, Chernobyl, all the other places that are likely to become irradiated as climate change strengthens, causing vulnerable power plants to become damaged, conflict to increase, etc. etc."

“Paul, why is your new species of mushroom going to have an impact in irradiated places?” She finds her breath becoming shallower and more rapid.

“The paultsake, I was going to call it.” He looks at her. “We found it in the waters around the power plant. Little tiny mycelium that were growing mushrooms about this size—" he raises his hand and shows her a space the size of a dime—“in the soil near the waters. They consume and disperse radiation. Powerful amounts. Such that the Sievert reading in the waters around the reactor was minimal. They use melanin to do it, the same damn stuff we have in our skin that protects us from UV rays. Wild.” He shakes his head. “I’d just gotten the results back from a test I'd been doing on the mushrooms when—“ he claps his hands together.

L opens her mouth, then stops. A psilocybin mushroom, she thinks. That’s what he looks like. A psilocybin mushroom man, come all this way to blow our fucking minds. She breaks into peals of laughter.

xxxxx

Part Six

The bryde whale with the timer on its back is not leaving the harbor. It swims a wide ellipse all afternoon, its gray back glinting in the sun. Ivy, George, and L stay out in the boat for more than an hour, listening to the sloshing of the water against the boat and waiting for the whale to breach again, which it does every twenty minutes or so, slowly drawing itself up out of the water, high enough that when it comes back down it sends a swell their way that makes the boat rock. It's as if the whale is showing off the timer, which L comes to realize looks like a giant 1980s-era Timex watch.

By the time they return to the beach, a crowd of about twenty people has gathered. As George, Ivy, and L walk onto shore, the crowd remains silent, tight with anticipation.

Finally, Tess, a biologist, speaks. "Was that a fucking whale? I saw it breach near you." She is a nearly six-foot tall, wiry southeast-Asian woman with bright eyes, a shaved head, and a scratchy voice. Back in regular life, her job was trekking through jungles looking for some of the most poisonous snakes in the world, then harvesting their venom for research.

George shrugs. "We were observing the crates when it showed up with that timer on its back."

"Timer? Is that what it is?" a middle-aged Australian woman says. "We can't read it from here."

"That’s what it looks like,” Ivy says. “When it showed up, it read 7:23:55.” She turns her notebook around, shows the group a drawing she did of the whale. "Next time we saw it, about twenty minutes later, it said 7:04:51." She shows them another drawing. "I think it's counting down."

"Fuck," says Tess. "So we have about eight days left to fix this place." The entire group jerks their heads toward her. She sighs. "Look, I've been here since the beginning. I know some of you have other theories, but I think we’re meant to clean up those dirty waters. I think it’s some kind of test, that’s what I think." She looks down as she talks, almost shy, but with a strong, unwavering voice. "We're all from 2019, right? 2019, a year in which the world is at risk of skidding into a runaway greenhouse effect. We're dipping our toes into the waters of the apocalypse. Well, this island is very nice and all, but out there—" she points—"out where the water goes dark, it's also apocalyptic." She pauses now, looks around, and finds the group rapt. "It's radioactive, dirty as fuck, and even hotter than it is here. I think we've been brought here because we're meant to learn how to save our planet. This is like a practice round. Like one of those hackathon competitions or something. Maybe, if we learn how to save this island, we'll understand how to save our planet too."

A murmur runs through the crowd now.

“So someone forced us to come here, just as a test?” scoffs a gray-haired tall American, who L remembers was a high school science teacher.

"I think she's right," says a middle-aged butch lady, a farmer. "I think we've all known this is what we're here to do, and we've been lazing around like we've got all the time in the world to do it--"

"We haven't been lazy!" someone yells.

"Ok," the farmer continues. "But we've been focusing on settling in, making ourselves comfortable. Surviving. Now we've been given a clear message. We have less than eight days to do what we've come here to do."

Some people groan and roll their eyes. Ivy and L share a glance. Could be right, Ivy seems to be communicating.

"Look, this whale could mean anything," says George. "We need to consider all possibilities. But I seriously doubt it's a message from some higher power."

"Not a higher power. It's a message from the Director," someone says.

"The Director?" L asks.

George sighs. "The Director is what some people have been calling the guy who—"

"Or the woman," says Ivy

"Or the woman," George says, nodding, "who, if Tess’s theory is correct, would’ve brought us here."

"Could be a group of people too," says Tess.

"Yes, but the point is we don't know anything about them," George says. "We shouldn't just be wildly guessing here, there's no point."

"But you're missing an important truth. That type of scientific skepticism makes sense back in the normal world, but it doesn't work here," says Pai, an older Thai woman, an artist. "Everything in this world has a reason. It is curated for us. From the supplies we were just miraculously given, to the perfectly temperate microclimate of this island, to this amazing weather we’ve been having."

"So, let's say you’re right," says L now. "We’re meant to fix the apocalyptic zone out there, clean up the water. What does that change? What can we actually do? What steps do we take first?”

The group falls silent.

Suddenly, Brendan, the silent hut builder, steps forward and waves his arms. Once he has the others' attention, he begins gesturing, pointing almost frantically, toward the water.

"What? Are you talking about the whale?"

He shakes his head, and then kneels down and begins writing something in the sand. "We need to retrieve the cr–" but as he writes a wave comes farther up the beach and begins to erase his work.

"I didn't see," some people shout.

He begins miming a box shape.

"He's saying we need to retrieve the crates. He's saying that's what we should focus on," says George. Brendan nods. "I agree," George says. "Look, it’s hard for me to believe in this Director character—I’m more of the camp that this is some sort of biological accident, that we all stepped through some wormhole or other—"

“It makes no sense!” says Pai.

“Ok,” says George. “But my point is that if you guys are right that we're being prompted toward certain activities, then yeah, it seems clear to me at least that we need to somehow retrieve those fuckin' things."

There's a moment of silence and George looks around at the group, sighing, a little out of breath from nerves, his eyebrows knit. L feels herself sweating. The afternoon sun is pointed directly at them now.

"Impossible," someone says. "They're radioactive."

"Yep," George says. "And we were beamed through space and time onto this fucking island."

It's as if the group has suddenly pointed themselves in the same direction, aligned with one another spiritually, and L can feel the energy shift into something powerful—the potential energy of a group of twenty or more people committed to a singular goal.

And then the building momentum breaks. "Fuck that," says a young Chinese physicist. “I’m figuring out a way home.”

The argument on the beach lasts until nightfall, until the hermit crabs begin taking over and the group decides to head back to the main house to prepare dinner. By the end of the day, it's decided that from this point on, the group would focus more on trying to explore Apocalypta, as they began to call the water beyond the fluorescent green, zig-zag border. And, while a contingent of them would work on retrieving the crates, the other, more spiritually minded contingent, would work on searching for signs from the Director.

Part Five

It feels right to be out on the water again. Back in her old life, L spent nearly every morning on a long-tail boat going out to a dive site. That half-hour ritual had always allowed her to collect her thoughts, the noise of the gas engine drowning out everything but the waves, the wind, and the sun. A morning boat ride meant she was on her way to do something worthwhile.

But there is no sound of an engine here. Only the creak of a metal boat, and oars slapping the water. And instead of soaring along, Ivy and George are slowly rowing them toward the astonishing border, which shines fluorescent green against the bright blue sky.

Their progress is strained, because as they approach the threshold, the current resists them. George's hairy back begins sweating profusely, but Ivy has covered up well, in a hat and baggy white shirt.

When L shields her eyes, she can see a tiny wave, maybe 15 centimeters high, zig-zagging along the border. She tries to think of scientific reasons for this--underground columns perhaps, but nothing, nothing about it seems natural.

They stop rowing. By now, she can see what those shapes are that she'd noticed from the shore. Islands of plastic crates, painted a neon gold that glints in the sun. Behemoths, guarding whatever lies beyond.

"What's in all these crates?"

"We haven't been able to figure that out," says George. He digs in his bag and removes a handheld device with a screen on it. He swipes his thumb across it to turn it on and, after a moment, a reading of ".3" shows up. "It's not safe to go check them out."

"What's that?" L asks.

"A geiger counter," says Ivy. "You have to take one when you come out here."

"Is .3 safe?" L asks.

".3 sieverts isn't great, but for a short period of time, we're fine," says George.

"What about closer to the border? Does it change?"

"Oh yeah," says Ivy. "It gets much worse. Actually, George had wanted to take another reading of the levels closer to the border. But we don't have to if you're not comfortable."

"Well, if you guys are sure it's safe enough. I mean do you know for sure how dangerous it is? I don't mean to be rude, but..." How reckless are we being here?

"Well, yeah, I do," says George. "I'm a nuclear engineer."

"Oh, well that's pretty fuckin' handy," says L.

"Yeah, pretty much everyone who arrives here has some kind of highly relevant skill," says George. His tone is nonchalant, but his expression communicates otherwise. It says, yeah, isn't that fuckin' creepy?

"So," says L.

"So, the last time we rowed up to the border, it was at 5 sieverts per hour. That's pretty damn high. If we stayed at that level for an entire hour, at least one of us would die within a couple weeks."

"Woah," says L.

"But, when we take a reading, we just row up to it quickly, stay there for maybe 5 seconds before rowing back--the levels fall really quickly down to a safe level. So we end up getting a dose of like .007. That's like...4 CT scans?"

"Ya know what? I think I'll go for a swim," says L. "Let you guys do your thing."

"Totally cool," says George.

L hops out of the boat and swims a bit toward the shore. George and Ivy give each other a look and then row three times, moving several meters forward before bobbing back a half-meter. L sees Ivy record the reading in a small notebook and then they quickly row back toward her.

"What'd it say?"

"4.9," says Ivy. "About the same as last time."

L pulls herself back into the boat. "So now what?"

"Typically," George says, "We row to a safe area and then we just chill. It seems pretty obvious that we need to go check out those crates, but there's no way to get out there. So we've somehow got to bring them--"

"To us," says L.

"Exactly," says George.

"Won't they be radioactive?"

"We'll see. The radiation could fall back down past the border zone, we don't actually know. That black water could be totally safe."

"It doesn't look like the safest water," L says. As a SCUBA diver, the opaqueness of the water beyond the threshold horrifies her at a deep level.

"No," says George. "But, even if the crates are radioactive, there's ways to clean things to make them safer to handle."

"Gotcha. So now, we just think?"

George turns up his hands. "Nothing better to do really."

They row back to an even lower radiation level and Ivy gets out her drawing supplies. The sun is really out now. L wishes she'd brought more cover. In her haste, she didn't even bring a hat and is just wearing her bathing suit top and shorts. "You try a magnet?" she asks.

"We'd need a pretty fucking powerful magnet," says George.

She has no other ideas. "Well, what have you tried?"

"Uh, nothing?" says George. "We've mainly been setting things up, trying to survive. Ivy and I only recently started trying to come out here regularly.

They sit in silence. After awhile, Ivy has drawn a striking image of the border, capturing with her colored pencils the near exact shade, and fluorescent nature of its glowing green. Finally she puts the sketchbook down. "I guess we should head back soon," she says.

"Wait," says George. "Just give me a few more minutes." L notices that his brow has furrowed and his whole body has become still. He stares at a single spot in the direction of one of the crates.

L follows his gaze. After a minute, she sees something. Or did she? A ripple in the calm black water. So small she doesn't say anything. But then, a minute later, the three of them gasp. Back beyond one of the gold crates, something emerges out of the water and then dips back down under it. A whale, or a shark, the hint of its shiny grey back standing out in stark contrast against the onyx of the water. But there was something strange about it, something on its back.

When it appears again, it's much closer. L sees now that it has a band around its torso, a wide, black rubber band, and attached to the band is something, something with a screen and flashing red figures. "It's a bryde whale," says L, noting the tall, falcate dorsal fin, and now, as it resurfaces again, the three characteristic head ridges. Again, a whale endemic to the Gulf of Thailand, one she would have no trouble identifying, even though she's seen them only a handful of times.

The three of them are frozen as the whale approaches. The next time it emerges, it breaches, straining up out of the water, higher than it seems it should be able to go before it slams its gigantic body back down, creating a huge splash, the edges of which reach their boat and provide a cool relief to L's burning forehead. Her breath is shallow. On the screen were numbers--what were they?

Now the whale resurfaces and skims the surface only 10 meters away. They can see clearly its message now: a clock, counting down: 07:23:55.

Part Four

After her conversation with Ivy, L walks down to the beach and digs a shallow hole. She lies down in it and imagines she’s her old family dog. She sniffs at the salty air and tries to slow her heartbeat. As the sun begins to set, she falls asleep.

She wakes to a touch on her shoulder. It’s George, standing over her, bathed in the waning green light coming from the horizon. Next to him is a squat, bearded man with an inscrutable expression.

“Sorry!” George says. “We just thought you should probably get set up for the night! This is Brendan, our resident tent-builder.” The other man sticks out his hand and L shakes it. “Brendan doesn’t talk,” George says. “He used to be able to before he arrived, apparently.”

Brendan nods once to confirm.

“Want to go pick out your home base?” George asks.

L nods, though the word "home" makes her want to run into the ocean and start swimming.

They meander through the jungle until L chooses a spot. It’s about five minutes up the path on the side of the house, next to what can hardly be called a creek: a thin stream of water running over some rocky dirt at the bottom of a manmade ditch.

L watches and occasionally assists while Brendan builds her a temporary tent, using tarps and bamboo poles. He communicates to her via gestures that she will have a hut like the others within a week. After a while, L points to his mouth and turns up her hands. He shrugs, then opens his mouth wide and pushes in his diaphragm. The noise that comes out is barely a moan, riding high on top of a wind of breath.

"So, you can't even make noise really?"

Brendan nods.

By nightfall, they have made a teepee with a lower skirt as well as a top skirt, which can be removed to allow for airflow on nights when it isn’t raining. It’s hard to say whether exposing herself to the island’s mosquitoes is worth the breeze. That night, she falls asleep as soon as she lies prostate on her loaned sleeping bag. In the morning, she finds herself scratching a sore into her thigh. She is covered in bites. Throughout the day, the others chuckle at her thick welts and constant scratching. They tell her she will get used to it. Besides, they say, no one has gotten any mosquito-borne illness so far, so she doesn’t need to worry.

Over the first few days, L keeps her distance from the others. Since they don’t push her to join in on their activities, she gathers that she is probably behaving pretty normally for having recently teleported. Meals are served communally and L gets in the habit of taking an aluminum plate out to the beach to sit alone. To avoid the others who work at the beach lab, she walks a kilometer or so to a bamboo dock, to which a small metal boat is tied.

She spends entire afternoons studying the line where the radioactivity begins. The water close to their island is clear, but several kilometers away, near the land on the other side of the bay, the color changes. After a flourescent green threshold, the water looks black. In it, she can see vague shapes bobbing up and down.

In the evenings, the tide moves out, revealing a biodiverse, shallow, littoral zone for a dozen meters out. L puts on a pair of too-big water shoes available in the main house and goes exploring. She is careful to step only on rock and dead coral because the living reef here seems healthy and she doesn’t want to damage it. Crabs, sea cucumbers, and urchins abound. The pistol shrimp, which are mostly too small to see, make their presence known by a loud popping sound. She imagines they are protesting her and the others’ presence here, unnatural as it is, by shooting tiny guns. There is also a species of snake or worm that she doesn’t recognize, which darts out from under one rock to go hide under another. She chases it one evening for almost an hour, trying to catch it, but it’s too quick.

Besides idle observation, L sleeps. The fatigue that had come over her in the week before her teleportation seems to have only gotten worse. She estimates that she’s spending at least 12 hours a day in a deep sleep. To avoid the mosquito bites at night, she keeps her tent closed and often wakes up in a pool of sweat. It’s hot and humid here. Although she might have time-traveled or changed dimensions, it doesn’t appear that she’s left Thailand.

When the tide comes in, or when she wades out a little farther, she can see countless fish just by looking down into the water. All the regular culprits are there: butterfly fish, rabbit fish, damsels, groupers. These fish feel familial, as if they are the very same ones she spends hours looking at every day back home. Altogether, this biosphere is remarkably consistent with that of her home island, despite its being surrounded by filth and decay.

Especially at night, the beach is populated by a bevy of hermit crabs. When she doesn’t want to think anymore, she races two of them against each other, digging out mazes on the beach and taking bets against herself for which crab will win.

The thought often enters L’s mind that she has gone crazy. Each day, she asks one or another of the group to confirm for her the story as she understands it. They use different words, but convey much the same message. Everyone arrived suddenly without any clear directive, but with all the supplies they need to perform their vocations, even if it meant scrounging around the island a bit. She estimates there are around thirty residents in all. The mood among the group feels uncannily happy. As if, despite the existential horror, they are enjoying themselves. She wonders if she will feel this way after a while.

Toward the end of her first week, she is eating her breakfast by the dock when George and Ivy approach. George throws a bag of equipment into the boat.

“What are you guys doing?” L asks.

“We’re going out there,” says Ivy, pointing toward the bay on the other side. She holds a notebook and a pencil case.

“Isn’t it dangerous?” L asks.

“No one’s gotten rad poisoning yet,” says George with a shrug.

“It’s not dangerous as long as we don’t go over the radioactive threshold,” Ivy explains. “Would you like to join?”

Part Three

Just inside the forest is what appears to be a small village. All around her, wedged in between tall coconut and palm trees, are simple bamboo huts on platforms. There must be thirty or so, each of a similar size and design: a window on the left and a bamboo door. Inside the open huts L sees an odd assortment of camping pads, sheets, quilts, and knitted blankets.

Deeper into the forest, there is a large, two-story house made of adobe bricks. A gate closes off the first story, creating a crawl space and flood zone underneath the main area of the house. On the second story, there is a large porch, where electronics and various supplies are laid out. The place is porous, open-doored, an inside-outside place. It looks like it could be overtaken by the jungle at any moment.

As they approach someone shouts from inside, “Ahhh!!” Alarmed, L looks at her new host, eyes wide.

“That’s okay,” he says. “That’s just Ivy. She probably saw a snake.” He’s smiling again.

This guy is cheery.

She continues to follow him up the dirt path toward the house, looking out for snakes and other critters. On her island she’d grown used to keeping an eye out for certain pests: red centipedes whose sting is so potent you need morphine to deal with the pain, two-meter long cobras, sand flies whose bites took weeks to stop itching. But who knows what the dangers are here. She figures she can’t be too far from home, but something tells her she can’t be so sure.

My sense of direction is off. The iron in my nose is de-magnetized, as my dad used to say. Ha.

On the porch are several bamboo woven maps, upon which are arrayed a variety of tools; arduinos, wires, and batteries, as well as natural tools like coconut husks, banana leaf wrappers, and small structures made from bent sticks.

Inside the house several other scruffy humans stretched out on bamboo mats. Some of them are writing or drawing on paper, others arrange wires on small circuit boards.

“This is everybody,” he says, gesturing. “You’ll meet them all in a moment.”

Why do I need to meet all these people? Can’t you take me back home?

They all look up at her with the same genre of expression: empathetic despair.

She doesn’t feel despair, or rather didn’t. But now it creeps in, a worm that multiplies and divides again and again, until it has clogged up her brain, rendering her physiology sluggish.

George catches this in her eyes.“Let’s talk for a bit,” he says and motions to two lawn chairs in the corner beside a small table. They are within earshot of the rest of the group and it makes L uncomfortable. The word cult flashes again in her mind and she remembers the story of a woman two years back, found in the jungle on her home island. Barely twenty years old, trying to escape from a yoga cult, she thought she could take a shortcut through the jungle. A couple weeks later she was found dead, half-eaten by lizards.

“I know this is weird,” George says, and L notices for the first time that his voice is soothing, or rather that it has all the qualities of being soothing, while at the same time giving off an artificial effect. “When I first got here it felt like a dream, or maybe even a nightmare. I kept feeling like I would wake up soon and go back home. But…well…I’ll explain that part later. First thing you should know is that you’re safe and the people here are safe. These are good people. Generally they’re artists, scientists, engineers. Would you say you fit into one of those categories?”

“Biologist,” she murmured.

“Ah, a biologist. Interesting. The last four have been biologists, perhaps there’s a new species we’re meant to discover,” he said to her, but well within earshot of the others, who turned and raised their eyebrows in interest.

“What?” she says, out loud now. “What are you talking about?”

“I’m sorry, I know this is overwhelming at first

“Look, all I need is a phone!” she says firmly.

“We don’t have one here,” he says.

She’s getting ready to give up, walk back down to the beach and figure this out on her own. Get away from these weirdos. “Look,” she says. “I just got in a little bit of trouble SCUBA diving and need some help getting home. Are you going to help me get back home? Are you? If I’m being totally upfront with you, if I’m being totally fuckin’ straight, I don’t really know where I am or how I got here. I was SCUBA diving. I was under the FUCKING WATER AND NOW I’M HERE.” She’s got her hands on the arms of her chair now, more weight flowing into them bit by bit.

The room is staring at her now, but they seem unconcerned. George looks at her with understanding.

“I’m sorry,” he says. “We’re still figuring out how to welcome people. I know I was totally confused when I got here. You see, this is not a normal island. You’ve…well… teleported here. Or time traveled or something. We all did.”

She gets up, her knees slightly bending, her hands almost in fight stance. As she walks toward the door, the creak of her bare footsteps on the wooden floor fill the room. The others gaze up at her with the same sorry empathy they had for her before.

On the porch, the sun hits her hard and she begins running toward the beach.

What the fuck what the fuck what the fuck.

She plops herself down under a palm tree and puts her hands on her temples. Her headache is coming back.

After a few minutes a woman approaches her and sits down nearby. At first, L avoids her gaze.

“Um, if you want I can try to explain things,” she says after a moment.

L looks at her. This woman doesn’t have the wide-eyed look of the others. She's a thin Asian woman with round hipster glasses and an oversized cotton button-up shirt. For the first time, L realizes that most people here are dressed in ill-fitting clothes.

“So, uh, ok here we go. Well first of all, we don’t know what this place is exactly.”

"Very helpful," L says.

“But what we do know is that people started showing up here two months ago and we get a new person every couple of days. People show up on the beach in various states of undress, without any possessions. Last week, I was in the middle of taking off for a flight to Singapore, and then I found myself washed up on that beach, trying to breath through a nose full of sand. Another few people were SCUBA diving, just like you, when they showed up.”

She trails off, as if trying to prioritize all the information she has to convey.

“Also, we can’t really go anywhere else. We’ve built a raft to explore the surrounding sea, but we can only go so far. It's generally calm, but past a certain point it's full of jellyfish and trash. And there is some land across the bay, but it appears to be radioactive. This little island is like a Garden of Eden or something. Unlike everything else, it’s not radioactive and apparently, according to George and some of the others who got here first, there were all these supplies there, even when the first ones arrived. There is fresh water, and plenty of food to be foraged. The little kitchen off the main house was there, stocked with some basics. You can see we’re starting some gardens near the house,” she says, pointing toward rows of dark, humus-laden, bare earth, near the front porch of the house.

L wants to believe it’s a joke, or a dream, or something, but there is emotion behind what this woman says. If it’s all a trick, she’s buying in despite herself, at least for now.

“What the hell?” L says.

The woman widens her eyes and tightens her mouth, as if to say, yeah, pretty fucked up right? “I’m Ivy, by the way,” she says and shakes L’s hand.

“So what, were we brought here by some evil scientist or something?” L says, laughing.

“That’s our best guess right now,” Ivy says, to L’s shock. “But again, we don't know. Most of the others are scientists, and there were tools left for making all sorts of robots and shit. Perhaps someone wanted to see what we could do with this world we seem to be stranded in.”

“What do you do then?” L asks.

“I’m a cartoonist,” Ivy says with a shrug.

Part Two

She sits up and digs her hands into the cool sand. She’s right at the shore line and the water laps at her like a salt-seeking dog. She examines her limbs and finds no wounds, no bruises, no scraped skin. Her skull, too, appears unharmed. She is intact. Despite this, she feels weak and somewhat disoriented. Not knowing what else to do, she lies back and waits for understanding to return to her.

Probably this is a remote beach near where we were diving. And…my team just thought I needed medical attention and that I shouldn’t be moved. Probably they’ll be back soon.

As the shock of being alive and in an entirely different place from her last recollection fades, she begins to re-inhabit her body and finds that the sensations are mostly bothersome. Sand in her shorts and a terribly parched throat. It’s the first time she notices that not only does she lack SCUBA gear, but her wetsuit is gone too—she's sporting only her shorts and bathing suit top.

A noise from inside the forest 500 meters down the beach sends a jolt of fear down her limbs. Moments later, a figure emerges. From far away, he looks like an early human: hairy, bearded, broad-chested, a bit of a lumbering walk. He wears khaki shorts with patches on them. She’s reminded of the tanned Russians she used to see camped out in abandoned tin mines on a secluded beach near one of the regular dive sights. They’d emerge late mornings, make fires, do laundry, and lay out in the sun as if ready to die, toasting evermore their already tan bodies. This guy has their look, but not their cool, relaxed posture. He walks exuberantly, then begins to jog toward her.

**

“Welcome!” he yells, cupping his hands around his mouth.

She starts to get up but feels light-headed again.

“Don’t get up!” he shouts, holding out his hands.

She sits back down, surprising herself with her subservience. Half-wondering if she should get up and run, she stays put.

My body must still be in shock.

Now the man is close. She sees that he is young, perhaps late-twenties or early-thirties, with an excited expression on his face. Nothing like those blasé Russians from the tin mines. He smells of sweat and soil. He kneels down beside her and extends his hand.

“Welcome. I’m George!” he says and she takes his hand and squeezes. A moment passes wherein she could give her name. “I don’t normally do this!” he says. “I’m not the one to welcome people, I mean. This is exciting!”

Sensing he needs to project more seriousness, he lowers his voice. “You seem to have retained your strength. Your muscles feeling okay otherwise? No aches or spasms?”

She shakes her head.

“That’s good, sometimes people come here with some decompression sickness,” he explains.

They stare at each other for a moment, both unsure of how to bridge the chasm of ignorance between them.

“I was foraging in the forest there and heard someone groaning a bit,” he explains. She doesn’t remember making any sounds. “Maybe that was when you were waking up?” he adds, intuiting her confusion.

“I think I got in some kind of accident. I don’t fully understand,” she says finally, laughing a bit, awkwardly. “I’m just sort of trying to sit here and center myself,” she says, thinking maybe she could get this guy to leave her alone for a bit longer, give her a little more time to remember what the hell happened. Because whatever is happening it’d probably be best to figure out on her own. Right? You never knew what kind of Westerners you’d encounter in this part of the world. There wasn’t a small chance she’d landed on an island run by a yoga cult. Heck, there could be a guy just around the corner with ‘magic powers.’

“Sure,” he says. “What were you doing before you found yourself here?”

“Well, I was SCUBA diving. Or I thought I was. But I don’t have any of my gear with me. I think my team is probably nearby.”

He nods. “Once you feel okay to walk we should go back to the main house and we can tell you everything we know. Want to try to walk a bit?” he asks and puts out his hand.

“Wait, what do you mean everything you know?” she says laughing. “If I could just use a phone, I’ll call my office, someone should be there.”

He makes a sympathetic noise with his mouth that she can’t quite interpret. “Why don’t we come back to the house first thing? You see—you’ve landed on a pretty peculiar little island here. I’ll explain everything back at the house. We’ve got great people there that can take care of you. So please, it’s just a five minute walk into the forest. Let me show you.”

Definitely a cult. Oh well, maybe they’ll have a phone at least.

She hoists herself up, declining his proffered hand. They begin walking toward the forest. She expects to hobble a bit, to stumble maybe, but instead she feels lithe.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Part One

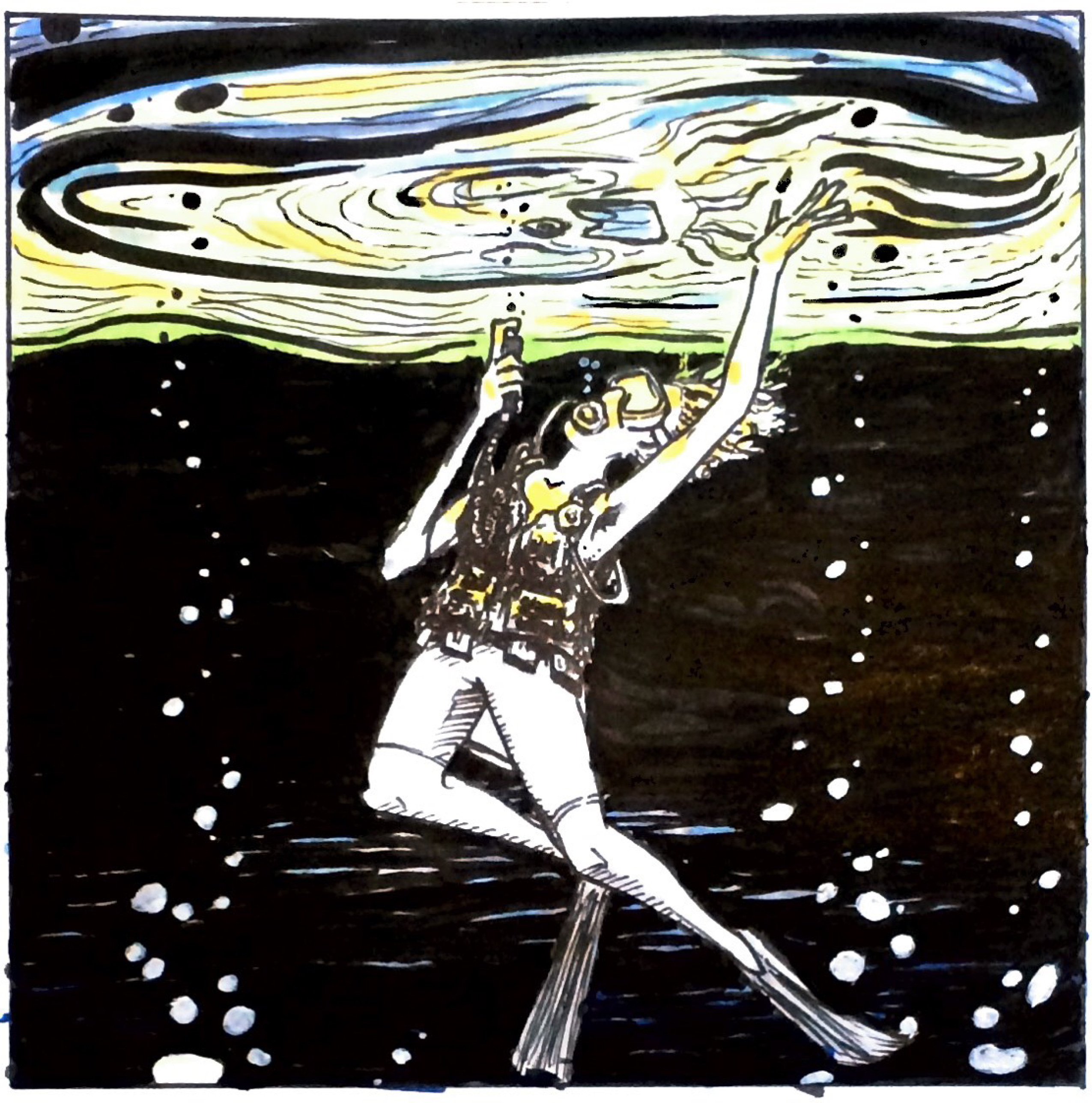

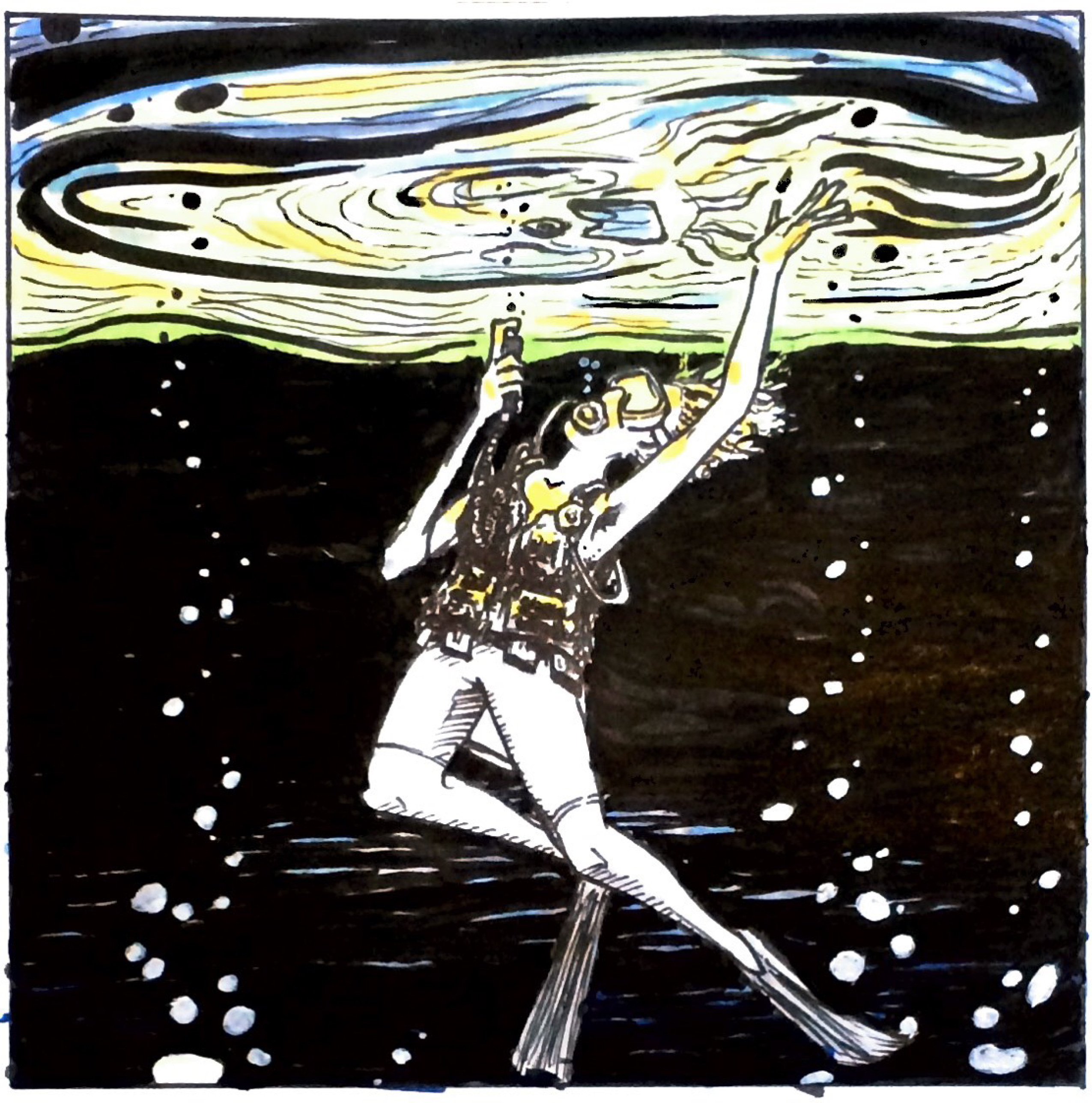

Lately, every time L ascends, she feels on the verge of passing out. About two meters from the surface, she finds herself needing to grasp onto the inflater nozzle of her BCD in order to remind her body of the task at hand. The water squeezes her, the churning, womb-like sounds surrounding her and disorienting her. The sun, filtered by the water into individual rays, hits like a spotlight, causing her to shield her eyes even as she felt herself hungrily drawing toward it.

And now, once again, she finds herself on the surface, back in her right mind, back on solid ground, which is in fact the choppy surface of the water. The sun steady, the physics standard. Escaped. Just a weird sensation was all.

Ever since she was a beginner diver, she’d felt a whiff of this sensation, but in the past few weeks it’s become stronger every dive. Glancing around to check that the interns she's been diving with are well, she actually wonders—if she were to let herself go on autopilot during ascension, allow her mind wander even just a bit, would she make it? Or would she pass out, sink to the bottom, die immediately?

What an unscientific thought. Likely she was becoming dizzy as a result of a slight physiological malfunction. An inner ear issue. Or maybe it was simply that this feeling mimicked that of not wanting to wake up from a good dream—it was so peaceful under there after all, so cozy, meditative. Your mind couldn’t be scattered. The water directed your focus, plied your attention toward what it wanted to show you.

“My god, I know how you feel,” her colleague, E, tells her as they unsuit back on the boat. E grunts as her tank clinks into its holder. “Sometimes I just don’t want to leave that world.”

“Maybe that’s all it is,” L replies, but still she can’t explain why the sensation is getting stronger, or—could she say—worse?

**

Two hours later she is entering the day’s data into the Thai governmental database. On that morning's dive, she and her team of interns completed a fish survey and noted this bounty: forty-five butterfly fish, nine bream, five parrot fish, three angel fish, twenty-five wrasse, forty-five cardinal fish, and one soap fish. Still much fewer snapper than she’d like to be seeing, but the other fishes were doing well.

E types away beside her, probably messaging with a prospective intern: an eager undergraduate or beleaguered graduate student, looking for a suitable research site to host them as well as an exciting Southeast Asian experience. A storm has rolled in. L’s nostrils are alerted to a metallic smell as large raindrops begin to fire away on the roof like they mean to put a hole in it. She feels as if the space has become smaller, as if the world would be happy to do them in.

L leans her forehead on her hand, rubs her temples. “I’ve got a bit of a headache now,” she says. E turns toward her and frowns.

“Take a paracetemol,” E says and, sighing, turns back to her computer. Then she groans. “This student wants to bring his girlfriend. But she’s not going to do any research. She just wants to hang out.” She rolls her eyes.

L gets up and heads to the kitchen to get a drink of water. On her fourth step, a curtain comes over her vision and all she can see is black. “I’m going blind,” she says as she collapses to the floor.

When she wakes up, E is standing over her. Her face looks old, and the geometry of it evokes an ancient math. L is sure, then, that there have been hundreds of people throughout human history that looked exactly like E.

And then she feels her heart beating faster than it should be beating. Her breath is deep and rapid at the same time, as if she can’t get enough air. But she respires, her heart beats, and she can see.

“I’m okay,” she says.

“My god, what is wrong with you?” E yells, her Russian accent really coming out now. “Do you want me to call an ambulance?”

“No, no,” L says. “I just stood up too fast I think. Something a little off with my circulation lately, maybe my blood pressure.”

Maybe I’m fucking pregnant. Fucking pregnant, that’s a funny phrase.

“My god, go home,” E says. “Take the day off.”

“But new students are coming, I have to orient them.”

“Honey, you need to take some time off.”

**

A couple hours later L is in her house, in her bed, inside the mosquito net. Her headache has faded and she feels fine. The storm has passed away, leaving behind thin, shifting, planes of air. She’s reading a dense, poetic book about water and how to interpret it. She’s enjoying the language, but can’t process much meaning from it. She puts the book down and looks at her nightstand. Two pregnancy tests rest there, staring up at her with two blank eyes. No results.

How is this possible?

Pregnancy was unlikely, as she and her various partners on the island always used condoms, but you never knew. So she could understand a positive result and she could understand a negative result but a non-result was perplexing to say the least.

Just a little low on iron from my last period. Something, something like that.

It is barely five o clock. A breeze blows in and a rodent scampers across her roof. The cicadas are quieting down to a low, tired, scratching, only needing to cool themselves down a little in this breezy landscape.

“We will look at water as the subject. Mammals and insects are interesting, but they will only earn their place in this book to the extent that they can explain the behavior, the signs and symbols of water.”

She puts the book down and falls asleep. She sleeps 12 hours. At 5 am a gecko lands on the wall of her bungalow just outside her head and calls out, loud and clear, “unh unh, unh unh, unh unh,” and she jolts awake, thinking the gecko is in her bed, that someone put it in her bed to wake her up, but there’s no one in her house, not even a gecko.

She can’t believe she slept 12 hours.

Maybe I am fucking pregnant.

Suddenly she feels tough and lichenous, tucked away inside herself from whatever might be happening outside.

**

On her motorbike drive to work, a rabid dog lunges at her, causing her to swerve sharply. After driving off a safe distance, she stops and looks back at it. It lies in the middle of the road, sunning.

She gets to the lab before E and spends a quiet morning drinking coffee and looking over the data. The coral bleaching is getting worse and what to do, what to do about that. 50% bleached already and it’s only the beginning of the hot season. At some point in her meager little life, she’d decided that the best thing she could do was have this field station and report the data. Tell the authorities. Alert people in power. Bolster the science, strengthen the argument. Not shut up. Perhaps she should do more.

E enters the room with her arms full of bags and various other attachments. Her motorbike helmet falls off her arm and rolls toward L. E's eyes go wide and she feigns anger. “My god, what are you doing here?”

“What do you mean?” L says.

“I thought you’d take the day off.”

“Oh I’m fine. Got a good night's sleep."

E tuts and shakes her head reprovingly.

**

Two hours later they’re diving again. It’s been determined L will be divemaster for two of the more experienced students and E will take the newbies. That way, the experienced students can cover some of the more routine data gathering and L can be free to focus on her pet research project, which tests whether smaller solitary corals are less resistant to bleaching than larger solitary corals.

E's group lays out the transects while L and her interns hang back and look at coral. She breathes out and sinks closer in to some branching coral, the home of twenty or so baby, white and yellow butterfly fish, who dart in and out like bees. She wishes she were doing a fish survey so that these lovely, tiny fish could be counted. If only their presence could be felt, could matter in the world. But probably they don’t care either way, probably that doesn’t matter to them.

Now it’s time to go and she motions the students to go ahead of her. With the lab's underwater camera they take a picture of the transect measuring tape every 50 cm. Back at the lab they will need to go through every one of these 300 pictures and identify the coral just to the left of the transect. She removes her underwater slate from her BCD pocket and begins counting. Everything is slow, deliberate. It’s arduous counting all the solitary corals—there are so many. The students’ frog kicks are too frequent, they are going too fast—almost out of her sight now. No matter, they are safe and experienced. She finishes her survey and meets them at the end of the third transect at 50 minutes into their dive. Together they reel up the transects, spiders assuming the thread of their web back into their abdomens. She directs one of the students to take the transect bag and hook it to her kit. The three of them look at each other in the eyes and L makes the hand signal for “let’s ascend”—a thumbs up.

She doesn’t think about that strange sensation. She’s thinking about the data she gathered and about what conclusions she might begin to draw. Slowly, slowly, she swims up, not even needing to think about moving her feet, just willing herself up. And then, at three meters from the surface, once again, it hits.

**

The pressure is more intense this time, the movements of the water like a thousand little flies distracting her attention. The light hits and she feels the heat of the sunrays on her body. The rays form a cone, which twists around her, and she is an unwilling dancer, moving her limbs oddly, floating six inches above an empty stage.

And then she is elsewhere. Her face is naked—no regulator. She feels sand in her nose and on her lips. She sputters, rubs her nose with her index and thumb, sticks out her tongue. Opens her eyes. She’s on the beach. Or a beach, rather. She doesn’t recognize the topography of this beach, with its thick forest, its meters of white sand. All the beaches on her island are short, with sparse, low vegetation and pieces of trash strewn about. This beach is pristine. A breeze tumbles down the white sand, unobstructed by a single other person. She is alone.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx